Some tension arose when Donald Trump spoke negatively about Somali , largely because identity is understood and constructed differently across communities. In the United States, race is commonly interpreted through a Black–White framework shaped by the historical legacy of slavery and segregation. Many African Americans are descendants of people who were forcibly brought to the country through slavery and, as a consequence, lost direct connections to specific ancestral homelands, languages, and ethnic identities.

In contrast, most Somali migrated to the United States with a clearly defined ethnic identity rooted in a shared language, culture, history, and homeland. This fundamental difference in historical experience and identity formation has at times produced misunderstandings and, occasionally, tension between communities.

Complicating matters further is the way Somali have historically been classified within Western racial frameworks. In older European and colonial-era anthropology, Somali people were frequently grouped under “Caucasoid” or “Hamitic” categories. Although these classifications are now recognized as outdated they nonetheless shaped historical perceptions. Such categorizations were based largely on physical features, linguistic affiliations, and pastoral culture rather than modern genetic science.

Within Somalia itself, most people generally do not identify strictly as Black, White, or Arab. Instead, they identify as Somali, emphasizing ethnic, cultural, and national belonging over externally imposed racial labels.

Genetic studies indicate that a majority of Somali men carry the Y-chromosome haplogroup E1b1b, which is common among populations in North Africa, Europe ( Balkans ), parts of the Mediterranean, and other Cushitic-speaking groups in East Africa. This reflects the deep and complex population history of the Horn of Africa, shaped by long-standing regional interactions rather than simplistic racial divisions.

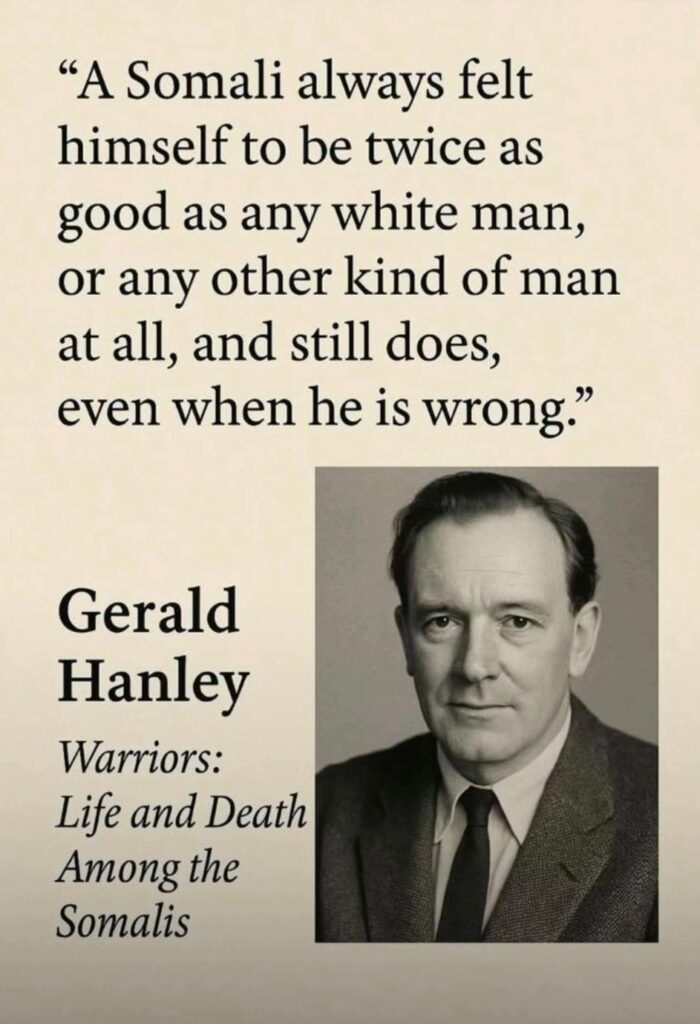

Historical accounts by European travelers and colonial observers—while often influenced by the biases of their time—frequently remarked on Somali social characteristics such as independence, pride, resilience, and resistance to domination. Writers such as Richard Burton and Gerald Hanley described Somalis as fiercely self-assured and lacking any sense of inferiority toward Europeans. Similar-observations appear in early twentieth-century colonial memoirs, which noted the absence of servility among Somali and their strong sense of equality.

Gerald Hanley, reflecting on his time among the Somali people, famously wrote:

“A Somali always felt himself to be twice as good as any white man, or any other kind of man at all, and still does even when he is wrong.”

Anthropologist Charles Gabriel Seligman, in Races of Africa (1930), classified Somalis within the so-called “Hamitic” branch of the Caucasoid race—a theory now rejected by modern anthropology but influential in earlier racial models.

Similarly, nineteenth-century European encyclopedias such as Meyers Konversationslexikon grouped Cushitic-speaking peoples, including Somalis, within broad Caucasoid classifications. These historical frameworks reflect past attempts to categorize human diversity rather than contemporary scientific consensus.

Even today, remnants of these older systems persist in some institutional classifications. For example, certain U.S. data-reporting standards, including those used by the University of California, list Somali origins under the “White / Caucasian” category for administrative purposes, particularly within the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) grouping. Such classifications are bureaucratic in nature and do not constitute statements of lived identity.

In recent years, some Somalis have begun to identify themselves primarily as “Black” within contemporary Western racial discourse. While this may reflect personal experiences or social pressures in diaspora contexts, it represents a shift away from the traditional Somali understanding of identity. Somali identity has historically been rooted in ethnocultural belonging—shared language, lineage, history, and homeland—rather than externally constructed racial categories. Adopting broad racial labels risks diluting Somalinimo and obscuring the distinct historical and cultural foundations of Somali identity. For this reason, greater emphasis should be placed on preserving and affirming Somali self-definition, rather than uncritically adopting racial frameworks that were never designed to accurately reflect who Somali.

Ultimately, Somali identity is not defined by American racial categories or colonial-era theories. “African” refers to a continent, not a race, and Somali identity is best understood as a distinct ethnocultural identity. Somali are Somali—shaped by their own history, language, culture, and long-standing presence in the Horn of Africa.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, no external group has the authority to define the race or identity of the Somali people. Identity is not imposed from outside but formed through self-knowledge, historical understanding, and cultural continuity. Somali must remain grounded in their history, preserve their heritage, and move forward with confidence and dignity.

While solidarity with others is possible, it should never require adopting identities shaped by external political struggles that do not reflect Somali historical experience. Identity must be approached with clarity and self-respect.

History shows that support and opposition do not align strictly along racial lines. During periods of political hostility toward Somali Americans, meaningful support came from diverse groups, including white individuals and neighboring communities such as Eritreans, Sudanese, and some Ethiopians.

Somali should take pride in their heritage and maintain their Somalinimo. External labels—Black, Arab, or White—cannot fully capture Somali identity, which is defined by shared history, culture, and self-definition.

SOOMAALINIMO

By Muna Kamila